– One possible interpretation of the exhibition –

“I don’t think of the Wunderkammer only as a concrete spatial-temporal moment in history, but as a theatrical concept that elevates themes that, in turn, inform and bear witness to different epistemes. From such a standpoint, cabinets of curiosities can be viewed as material manifestations of a sentiment based on the rejection of values of progress handed down by Enlightenment, reason and utility; this point of view elevates collection, classification, taxonomy, documentation and exhibition.”

(M. Endt, 2008, Reopening the Cabinet of Curiosities: Nature and the Marvellous in Surrealism and Contemporary Art, University of Manchester, p. 24)

In early May of 2023, the curatorial team of the Cultural Centre of Belgrade invited me, as the author of the “Cabinets of Wonders in the World of Art” monograph, to give a guided tour/lecture and review the “Unearthing the Collection” exhibition presented in its Podroom gallery, authored by Vladimir Bjeličić, Jana Gligorijević, Zorana Đaković Miniti and Siniša Ilić. The exhibition was organised as part of the current reflection on the collection of artworks exhibited at past October Salons in Belgrade. Thus, our protagonist, The OS Collection, joined by other descendants of collections of artworks and various other objects, immediately opens with the question of its purpose and the potential it has today, constantly reexamining the concepts of collectorship, transvaluation and the relationships between objects in the very moment they become a part of a given institution’s collection, as well as the question of the critique of the institution itself as the apparatus through which society thinks (M. Douglas, 2001: How Institutions Think, Belgrade: Fabrika knjiga).

Content with just touching upon these complex issues, I first turned to the history of the October Salon in Belgrade, as tumultuous as the history of the capital itself, from the foundation of this art manifestation in the early 1960s till today. Founded as the review of the best of the best, this annual, and then biannual exhibition has been undergoing transformation for decades, not only by following the trends of modern and contemporary art in the region, but also by reflecting the contemporary social and political relations. “By the initiative of the People’s Committee of Belgrade, a significant cultural institution – the October Salon – has been founded as part of the Modern Gallery, with the aim to exhibit the best works of our best artists every year, in celebration of the capital’s liberation, and, at the same time, to give the most complete overview of ideas and qualitative advances in our art”. (M. Protić, 1960. Magazine Komunist, Belgrade: The Gazette of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia). Ever since, journeying across both the calendar (at times not being held in October at all) and the organising institutions and spaces that had hosted it – from the Cvijeta Zuzorić Art Pavilion at Kalemegdan Fortress, an exhibition space that has been replaced by a parking lot and a handful of galleries belonging to liquidated cultural institutions, to abandoned and condemned public buildings across the capital that would soon be imbued with new purposes and values – the October Salon, presently organised by the Cultural Centre of Belgrade, changed its conception many times and, throughout its existence, managed to represent almost all nationally and regionally relevant artists. Hence, the initiative to collect the artworks exhibited at the manifestation is a prudent and logical next step, especially if we consider this increasingly rich collection to be a witness of the times. It has been growing since 2011, when Jan Fabre gifted his piece to the Cultural Centre after the 51st Salon, and now consists of more than 140 artworks. The CCB’s website offers an excellent insight into its documentation. Naturally, as a researcher, after I’ve used it for the first time, I’ve been grateful to the colleagues who have created and published the database.

However, despite the significance of documentation and the practice of safekeeping for the purpose of safekeeping, it feels impossible to ignore the question: and what is to be done with the collection? How do we communicate through it today? What are the meanings and relationships offered by this extensive group of re-contextualised artworks, stored in the depots of a cultural centre? How are they to be selected going forward, what are the criteria to pick those, amongst all those exhibited at the October Salon in the future, that will finally be part of the collection?

By the token of their faith in the power of the contemporary artist and curatorial gesture, the CCB’s team successfully offers potential answers, or at least deepens the questions posed by the project “Collection of Decades”, which served as the framework for the “Unearthing of the Collection” exhibition running from 11 May to 17 June 2023. Approaching the collection with a desire to discover, as well as a palpable sense of wonder, or astonishment as it discovered the multitude of its layers, the curatorial-artist team espoused the Wunderkammer methodology, i.e. a special exhibition model that coopts the exhibition meanings and characteristics inherent to the cabinets of wonders.

As magnificent collections of the most diverse objects, the cabinet of wonders, or curiosities, were quite popular in Western Europe during the Renaissance and Baroque. Artworks and relics, samples of flora and fauna, various human creations, as well as written works – all of this would be collected in the same place as a whole lending itself to erudite study, but also to its owner’s representation. These accumulated objects could have been exhibited in a cabinet, a special box, a study, or in huge castles of famous nobles. The collector, wanting to gather all the knowledge of the world in a single spot, and tame and subordinate time and space, freezing the inevitable progression of life and history, would become the sovereign of his own personal microcosm. Every collection, seemingly chaotic and filled with objects piled up and placed in illogical relations, corresponded to the relationship of early modern man to knowledge and efforts to understand the world surrounding him. Juxtaposing objects spurred observers to both physical and mental wandering filled with a desire to discover. As the relationship to knowledge transformed in the Age of Enlightenment, so did the cabinets of wonders, becoming, on the one hand, collections of artworks, minerals and natural species, technical and other collections of modern museum institutions, and, on the other, spaces for experiments and scientific discovery. The interest in collections of curiosities and the premodern aesthetics of the curious reappears in the early 20th century, after the disappointment in the promised progress of modernism and exclusively rational forms of knowledge caused creators – first through poetry and then through fine arts, too – to return to the aesthetics of the curious and the tendency towards the subconscious and the abstruse. Therefore, the models of juxtaposing objects in the technique of collage, assemblage and complete installations can today be grasped in this context, as well, while the works of artists such as André Breton, Joseph Cornell and others are immediately considered and related to the concept of the cabinet of wonders. Finally, contemporary curatorial and artistic practice are, no doubt, increasingly reliant on this phenomenon as a method of sorts, a possible means of thinking about dominant value systems, and a tool of institutional critique.

Relying on the legacy of the cabinets of wonders as a kind of an image of its owner’s world, although in the context of thinking about the October Salon Collection, the curatorial-artist team begins with the question about the image of the world today, but the very title of the exhibition – Unearthing the Collection – suggests a critique of institutions (the museum) and Fred Wilson’s “Mining the Museum” intervention. From the standpoint of the history of museum and artistic practice, this significant, perhaps even revolutionary act took place in 1992 at the Maryland Historical Society, when Wilson confronted previously unseen objects related to slave ownership, stored in the museum warehouse, to the permanently exhibited objects, which represented the bourgeois, white population. This has been his way of grasping the questions of social relations and the selection of images of a community, which has intentionally consigned certain segments to oblivion. These very questions have remained relevant and universal to this day: what is the image of the world brought forward by museums as the representatives of a history written by the victors, and what of the individual histories, the common lives? What is the (potential) role of art in this context and could we, once more, find ourselves on the cusp of great breakthroughs? By mining the depot of the Cultural Centre of Belgrade and exhibiting its fragments in Podroom (a space itself associated with piled up objects gathering dust), the curatorial-artist team, however, poses questions of oblivion, relevant for the local context, i.e. the questions of re-actualisation and re-evaluation of the past kept safe in the collection grown over the past decade. The permeation of the issues of revolutionary change in the world (of art) and the role of the individual is clear at the very beginning of the exhibition, by the virtue of two overlapping artworks. Already at the staircase leading to the basement, the photos of chairs used in educational institutions, with visible marks left by previous generations (Milorad Mladenović), meet the video artwork by Zoran Popović, “The Gestural Speech of Joseph Beuys”, a recording of the 1973 performance-lecture by Beuys, dedicated to Anacharsis Cloots, an active participant of the French Revolution. After recording and editing this performance, Popović exhibited it several times in the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade (in which, precisely in that decade, the local contemporary art scene was making its breakthrough), and, in 2016, added Richard Wagner’s vigorous music to the digitalised version of his video artwork.

With our head still ringing from these tunes and images of the past, we soon encounter the soft sculpture by Ana Krstić, whose shapes and shadows invite further exploration, albeit with a title that clearly states there are no simple, easy answers: “We don’t know what it is, but it’s definitely not what you think it is.” With such an introduction to the exhibition, the visitor can go down the path offered by Siniša Ilić: “The purple thread connects all exhibited works, mapping them in space as a sum of curiosities with multifaceted potential”, or discover relations in the chaos of exhibited works on their own. My own review moves on to Dadaism through Vladan Radovanović’s piece, with the curatorial gesture of juxtaposing Dubravka Sekulić’s audio installation with Jukka Korkeila’s drawings characterised by a relation of allegory, usually seen in relationships between objects in cabinets of wonders and modern-age assemblages. The room that hosts “ The Old Lady”, that is, the Geozavod building in Belgrade’s Savamala (Dubravka Sekulić’s work), in dialogue with Jukka Korkeila’s site-specific spatial installation “Nothing Lasts Forever” – specially re-contexualised for the occasion – leads us to think about pressing social-political and spatial questions of a new urban panorama that has no room for this symbol of the capital’s modern age. “I was built as a centre of commerce and future finance. The heart of an important capitalist state. In a posh neighbourhood. A single glance from the Hotel Bristol, across the street, would make me flutter with expectations of the good life that was to follow. What a mistake that was. In my, umm, age, the only thing I’ve been always certain of is that plans are made for one direction, while reality always takes another.” (transcribed segment of Dubravka Sekulić’s audio installation “The Old Lady”).

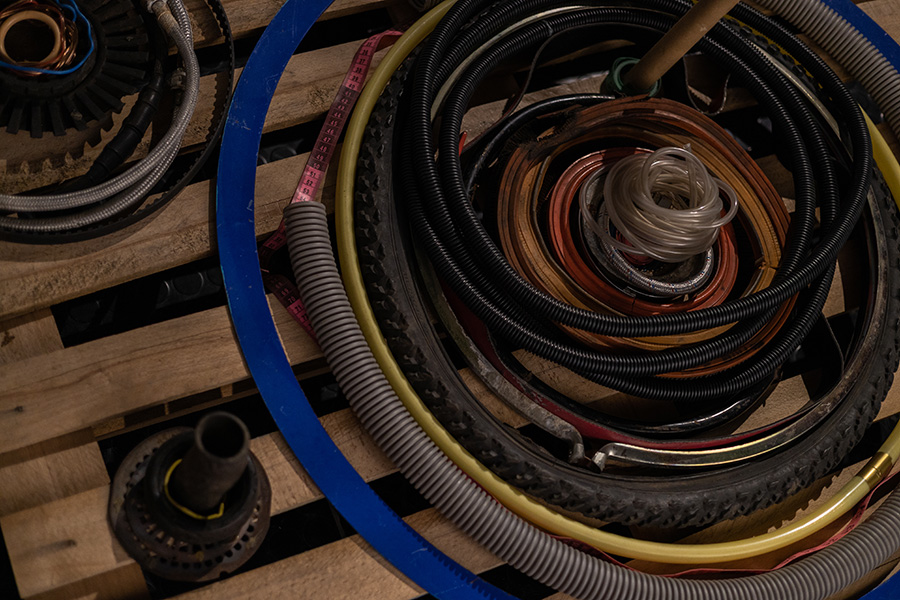

Vuk Ćosić’s “Unboxing” video performance suggests that permanently tumultuous circumstances impact the individual, who often succeeds in embodying their own identity only in a personal microcosm constructed against the backdrop of great, official histories. The replica of Duchamp’s Box in a Suitcase (Boîte-en-valise) – a peculiar medium of creative expression that was the reason the aforementioned Cornell and Duchamp met – is being meticulously unboxed by Ćosić in his home, in front of the library, with commentary on the context and the importance of this object and the books behind it. After moving away from Belgrade in 1991 due to the collapse of former Yugoslavia, this artist carried his personal library with him, ensuring the continuity of his self against the permanent change of scenery and context forced upon multiple generations in his family by social and historical conditions. In addition to Duchamp, the extent to which Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, Vlado Martek, Zoran Gavrić and other residents of Ćosić’s library shaped the creative gaze of this artist is matched by the influence exerted by the images of the collapse of all value systems and the social crisis in the 1990s. If the Renaissance collector had newly discovered continents to collect curiosities and as his spaces of wandering and discovery, the artists in this region, during the collapse of Yugoslavia, had landfills, abandoned factories and flea markets, full of discarded objects that lost their owners. They would collect the found objects, giving them new meaning and creating constellations of sorts, such as Vlatka Horvat’s work on the floor of the Podroom gallery: “Unexpected provisional constellations and encounters between objects and materials, taken from multiple different contexts, trigger an array of new associations which, in turn, construct surprising relations, with spatial hierarchies turned upside down.” (https://kolekcija.oktobarskisalon.org/sr/kolekcija-umetnik/vlatka-horvat/) This work reaffirms the thesis on the theory of rubbish by Michael Thompson, according to which prematurely discarded objects, instead of reaching a point of worthlessness and turning into dust, continue to exist in a so-called timeless and spaceless limbo, from which they can be retrieved by a creative individual and successfully transitioned to a category of objects with permanent value. Quite tellingly, he concludes that, in our contemporary age, “we must study rubbish, if we want to study the social control over values.” (M. Thompson, 1979: Rubbish Theory: the Creation and Destruction of Value, Oxford University Press, p. 10) Resembling a time capsule’s plating, according to the curators, Perica Donkov’s informel opens a space for the further contemplation of these problems. However, the presence of the contemporary moment and, as it unfortunately seems, an increasingly current segment of the image of our world, is beyond doubt as soon as we turn to Ivana Smiljanić’s spatial installation on the other side.

In an artwork titled “You’ll Remember Me”, the contours of a female figure in movement, filled out by fine print, appear in rows against transparent panels. The written text originates from a so-called “diary of insults”, sentences recorded by the artist from her own traumatic personal experience, or overheard in the street, on public transportation… “Out of context, they are banal, ambiguous, or humorous (“that’s a really nice idea”, “you must be thinking, if you’re married, you’re set for life”, “you’ll remember me”, “be happy you’re with me”…)”. The light behind the transparent panels creates a special atmosphere, along with the recorded voice of the artist that occasionally announces some of the written sentences with no emotion. “The author makes her voice heard by speaking out loud some of the sentences from the “diary of insults”, although that’s restricted to the handful of those that directly insult, humiliate and endanger the integrity of the person being addressed (…) These sentences are spoken word by word, with a total lack of expression, divorced from meaning, and so sound indeterminate, like a language course or a voice machine.” (https://kolekcija.oktobarskisalon.org/sr/kolekcija-umetnik/ivana-smiljanic/) The impression produced by both the artwork and its title in the age of frequent psychological, even physical violence, opens the questions: what do we choose to remember today, and what do we choose to forget, i.e. what is it that institutions and public opinion choose not to remember?

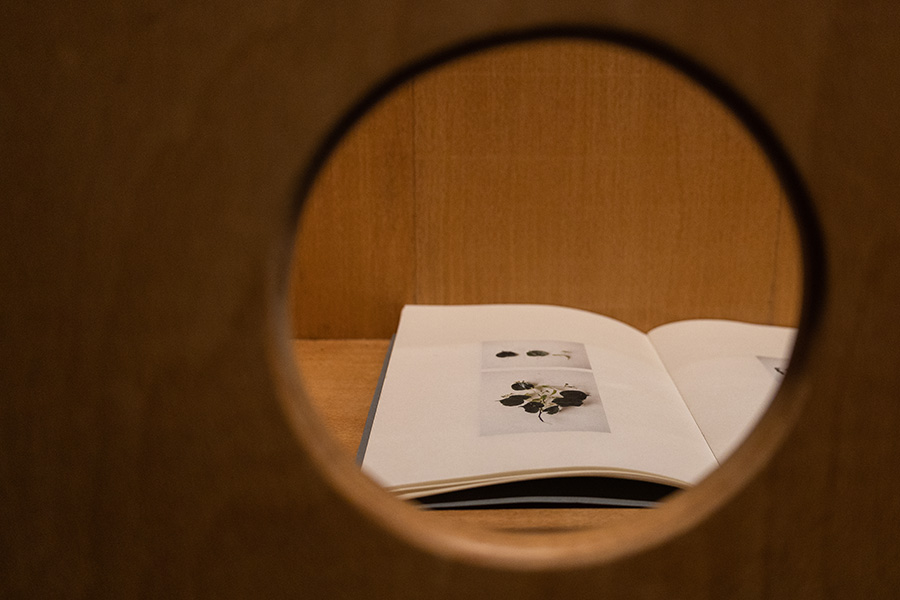

Moving on, while we use concepts such as: circular economy, green policies, environmental protection on an everyday basis, and simultaneously, on a global level, act contrary to the ideas conveyed by these concepts, the room dedicated to an attempt to return to nature completes the idea of the Wunderkammer, in which the natural and the artificial are equal components of the collection. The curators are, therefore, correct to put the herbarium on a pedestal, and the artists (Karla Mati, Dušica Dražić and Nena Skoko) create imprints of personal quests, struggles and tragedies in works created out of plants.

The purple thread finally leads to the work of the artist who arranged it. Siniša Ilić, with his film “The Passage to Reality”, takes us back to the beginning, to our protagonist – the OS Collection – and all the images of memory it keeps, and the potentials it reveals. The film was made several years ago, when the artist was invited to give his own view of the OS collection, from his own perspective, as part of the “Collection of Decades” project. “The artwork has several points of origin. The painting by Ljubica Cuca Sokić, located in an office room in the Cultural Centre of Belgrade, a series of unsigned photos found in CCB’s offices and a spatial interpretation of the theme of the work. The photos offer a collage-type insights into life in Yugoslavia and Belgrade, are of various quality and belong to various eras. Some of them display Tito and work actions, the construction and modernisation of the country, cultural events, and the life style of the latter half of the 20th century. While this material enables insight into the social context in which the October Salon itself lived and developed, the canvass painting by Ljubica Cuca Sokić, exhibited in an office room, poses a current question about the position of art – is it a part of the scenery, a backdrop for the complex processes of working in the field of – in this case – art and culture, but also politics?” (Siniša Ilić, https://kolekcija.oktobarskisalon.org/sr/os-57-vesti/kolekcija-decenija-u-panceva/) Cuca Sokić’s painting is symbolically moved to Podroom and added to this peculiar cabinet of wonders, embodied in the “Unearthing the Collection” exhibition, while the photos and scenes that the artist selected for the film can easily bring out additional layers in the interpretation of the artwork. It’s very hard not to give in to the impression that the Yugoslav heritage of Belgrade is inevitably losing its meaning, while the role of the OS Collection, contemporary cultural institutions, and art itself is to ensure that this heritage and all other layers of memory, with all the lessons they impart, are kept at least as fragments of the new image of the world.

In order to bring this to a close, we return – again – to the beginning. Although the exhibition ended with a public performance in which the artworks were brought back to the depot from Podroom, I hope the opened (or, at least, highlighted) problems and challenges will stimulate new theses that will continue to invite critique and reexamination. Finally, as a firm believer in the cyclical nature of all phenomena, my own trajectory of discovery brings me back to the beginning: to the online, digital base of the OS Collection, reaffirming my suspicion of a multitude of possible directions of movement – both through the exhibition and through the entire collection – and the dependence of the relations between the elements of the collection upon personal perspective, the human mind as a encyclopaedia of sorts, a cabinet of wonders filled to the brim with the images (of feelings/memories) that an individual tries to externalise.